By Jonathan J. Kalmakoff

In a hidden river gorge in the remote and rugged highlands of Samtskhe-Javakheti region, Georgia lies a grotto where, for nearly two centuries, Doukhobors have gone to seek solitude, consolation and serenity. It is also the site of one of the most momentous and tumultuous events in their history – the Burning of Arms.

The Peshcherochki (Пещерочки) is a place of extraordinary natural beauty and is imbued with immense historical, cultural and spiritual importance to the Doukhobor people. Indeed, it is considered one of the most sacred sites in Doukhoborism.

So when the opportunity arose to visit the Caucasus in July of 2015, I jumped at the chance to see and experience this holy and historic place for myself!

I accompanied a group of eight other Canadian Doukhobors on a three-week tour of Doukhobor settlements throughout the Caucasus. It was an exceptionally thrilling experience, visiting places steeped in heritage and tradition that I had only read about in books. Throughout our trip, I shared my knowledge of the historical significance of the sites with the other participants. Treading in the footsteps of our ancestors, it was a profoundly moving and meaningful journey.

After spending our first week travelling throughout northeast Turkey, we made our way into Georgia. We arrived at the village of Gorelovka, the largest of eight Doukhobor settlements on the Javakheti Plateau, a large, high-altitude grassland surrounded by the Javakheti Range or Mokryi Gori (‘Wet Mountains’). It was once the capitol of Dukhobor’ye, the popular 19th century name given to these uplands by Russian travellers and officials, owing to its predominantly Doukhobor population. The Doukhobors themselves called the plateau Kholodnoye, or the ‘cold place’ on account of its high elevation and cool climate. Today, however, the village and surrounding plateau is home to thousands of Armenian migrants, with only a hundred and fifty or so Doukhobors remaining.

Situated at the forks of two small rivers, Gorelovka comprised three long parallel streets, with houses aligned on both sides of each street. While many dwellings were occupied by newcomers, they still retained distinctive Doukhobor stylings, with sharp-pitched roofs, verandahs with decoratively-carved beams, whitewashed walls, and sky-blue trim on eaves, door and window frames. Some were clad in metal roofing, while others still had thatch. The Doukhobor yards were neat and orderly, with well-kept gardens and outbuildings; those of the Armenians were less tidy, with livestock kept penned and piled manure drying for use as heating fuel. The once-spotless streets were rutted and covered in cow dung as the newcomers drove their cattle over them to the hills and back daily. Above us, storks nested on the tops of power poles; a natural phenomenon unique to this village.

In Gorelovka, we met Nikolai Kondrat’evich Sukhorukov, Tat’yana Vladimirovna Markina and Yuri Vladimirovich Strukov. Nikolai, or Kolya, was a tall man in his sixties with inquisitive blue eyes and a long white beard. Having moved to Simferopol in the Crimea in the 1990s for work, he returned several years ago, desiring a simpler, more wholesome life. Tat’yana was a young woman in her late twenties with dark brown hair, warm brown eyes and a kind smile. Raised here, she left to attend university in Tyumen in Siberia, where she now worked as a geologist. However, she came back each summer to live in her family home. Yuri, in his late thirties, had a stocky build with blond hair and cheery blue eyes. Having lived for years in the Georgian resort town of Borjomi, he returned here because he felt it was a better place to raise his young family. They would be our constant hosts and guides during our stay, showing us tremendous hospitality and generosity.

We spent our first day with our hosts attending a moleniye (‘prayer service’) at the historic Sirotsky Dom (‘Orphan’s Home’) in Gorelovka, followed by a hike through the scenic countryside along Lake Madatapa, then an open-air moleniye and picnic beside the ruins of the 19th century khutor (‘farmstead’) of the Kalmykov dynasty of Doukhobor leaders. Of these remarkably memorable events, I will write separately.

On the morning of our second day, our hosts organized a convoy of vehicles from among local Doukhobors to take our group to the much-awaited Peshcherochki. Our driver was Sergei Mikhailovich Yashchenkov, an affable retired kolkhoz (‘collective farm’) tractor driver. Kolya also accompanied us on our drive.

As we drove west from Gorelovka along a pothole-laden paved road, the land was flat and divided into fields of oats, barley and rye. A kilometer to our north stood a large wooded hill. “The Spasovsky Kurgan,” said Kolya, pointing to it. This kurgan (‘mound’), I learned, took its name from the village of Spasovka, which lay on its opposite side. “There is much wildlife on the hill,” added Sergei, eagerly. “There, in its woods, one can find deer, wolves, fox and wild boar”. Sergei, it turned out, was an avid outdoorsman.

Within minutes, we arrived at Orlovka and turned south off the highway through the village. It was noticeably smaller and poorer than Gorelovka, with several houses standing empty and derelict along its single street. “My family once lived here” Sergei wistfully remarked. “But now, only two Doukhobor households remain.” Many homes, I found out, were taken up by Armenians after most Doukhobors relocated to Russia in the 1990s. The dilapidated state of the village left me feeling melancholy…

From Orlovka, we continued south along a heavily-rutted dirt road. The flat, cultivated fields soon gave way to rolling grassland. Herds of grazing cattle and sheep dotted the treeless landscape. To our west loomed a massive hill, if not a small mountain. “The Svyataya Gora,” observed Kolya solemnly. “It is sacred to our people”, he added. “Atop it lies the grave of a saint, a holy man.” Each summer, I learned, Doukhobors gathered to pray on this ‘holy mountain’ that marked the western boundary of Dukhobor’ye. Its imposing presence and enormity left a powerful impression on me.

After three or so kilometers, we turned off the road and drove cross-country to the east. Within a kilometer, we came to a stop on a broad, grassy plateau with rocky outcroppings. We exited the vehicle and surveyed our surroundings. Behind us, the Svyataya Gora dominated the horizon. In front of us, the ground dropped away precipitously, and we found ourselves standing at the edge of a deep gorge, staring down its steep, rocky walls. A small river ran along its bottom. “The Zagranichnaya,” explained Kolya, pointing to it. The Zagranichnaya or ‘transboundary’ river was so named because when the Doukhobors arrived on the plateau in the 1840s, its source lay across the Turkish border. It was here on the banks of this river where the Peshcherochki stood.

I was brimming with anticipation… We were nearing our destination!

Within minutes, we were joined by the rest of the convoy and soon our entire group was anxiously assembled on the plateau. Kolya then led us to the head of a trail, obscured by undergrowth, which gradually descended into the gorge. We slowly and cautiously made our way downward, single-file, along the narrow, rock-strewn path. As we did, the faint sound of trickling water grew louder as it tumbled over rocks and echoed off the gorge walls.

Once we reached the bottom of the gorge, I instinctively looked around and uttered an involuntary “wow”! The scene that greeted us was truly breathtaking. The dark, sheer sandstone walls of the gorge, 10 to 15 meters high, towered above us on one side. The Zagranichnaya babbled and rippled past us on the other. The floor of the gorge teemed with tall waving grass, patches of brush and scattered boulders, bathed in the rays of the midday sun. The far side of the gorge, 30 to 40 meters distant, sloped gently up to the horizon. It felt as though we had entered a different world from that above.

The place where we stood was a sharp outside bend of the Zagranichnaya which, over millennia, had cut into the surrounding rock to form the vertical cliff or cut bank overlooking us. The lower rock stratum, being comprised of softer, more porous rock, had been further eroded by the meandering river to form a shallow cave-like opening or rock shelter at the base of the cliff. Lying on a north-south axis, the cavity was a meter or so deep, two to three meters high, and over 80 meters long. It was entirely open to the outside along its length.

This was the Peshcherochki of lore and legend!

I paused to consider the Doukhobor name of this feature. It was derived from the Russian term peshchera, commonly translated as ‘cave’. This puzzled me somewhat, since it was not technically a cave, as its opening was wider than it was deep. However, I then recalled that the term also referred to a ‘grotto’ or ‘hollow’ which described the feature perfectly. It also occurred to me that though it formed a single chamber, Doukhobors always referred to the feature in the plural (Peshchery), and always in diminutive, affectionate terms (Peshcherki or Peshcherochki). Such was the uniqueness of the Doukhobor dialect!

Within the grotto, there was a deep stillness in the air that made the slightest sound – the buzz of an insect’s wing, the cracking of a twig, or the rustle of grass – distinctive and pronounced. Just beyond us, the hum of the river formed a soundscape of natural white noise that had a strangely soothing, relaxing and centering effect. And the mottled light and shadow that played upon the rock face evoked a sense of serenity and contentment. As I took in the sights and sounds of this place, my senses awakened and I felt a deep sense of peace.

Our group fanned out and began to explore the Peshcherochki. As we did, we learned from our hosts about the legends and traditions associated with it.

At the south end of the grotto, Yuri beckoned us toward a small, rocky alcove where an imprint in the shape of a hand could be seen. “Doukhobors believe it is the hand print of Christ,” he declared, “who hid here from his persecutors.” “At one time,” he added solemnly, “the impression was so clear that you could make out the fingerprints. But it became faded and worn over time by so many people placing their palms over it.” Accordingly, he asked us not to touch it, only to kiss it, which we did in reverence.

A few paces further, Tat’yana pointed out to us the word “Dukhobor” faintly inscribed in Cyrillic on the grotto wall. In another spot, three faded floral symbols appeared etched and painted on the rock. “Our people believe that these images have always been here,” she explained, “and that they appeared naturally and divinely and not by the hands of man.” We kissed them out of veneration and respect.

We then gathered around Kolya, who had halted along the grotto. “There is a legend,” he proclaimed, “that the Golubinaya Kniga is buried somewhere near the Peshcherochki.” The ‘Book of the Dove’, I discovered, was a mythical book in Slavic folklore said to contain all knowledge – the entire assembled wisdom of God. “Doukhobors,” he continued, “no matter how few remain, must carry out our mission to preserve this holy place and book, otherwise triple as much will be asked from us on Judgement Day.”

We slowly made our way to the far north end of the grotto, which was enclosed by a man-made facade so as to form a small khatochka (‘little hut’). The rock face naturally formed two adjacent walls, one running lengthwise and another spanning the width, along with most of the ceiling. Another two masonry walls were built along the opposite length (with a window enclosure) and width (with a doorway) with a masonry tile roof. The outward-facing exterior walls were whitewashed while the window sill, door frame and door were painted sky-blue. A rising sun symbol was inscribed over the entrance. Built by Doukhobors in the 19th century, it served as a place of prayer and repose.

We entered the khatochka and found ourselves in a small, dimly-lit chamber, 4 meters wide by 5 meters long, lined with low stone benches. The interior masonry walls were etched with floral symbols, while lush ferns grew out of the damp rock face. We lingered therefor a long while, lost in our own thoughts and prayers.

“According to tradition,” said Kolya quietly and reverently, “this was a favorite place of Doukhobor leader Luker’ya Vasil’evna Kalmykova (1841-1886), who loved to spend time here in summer in deep spiritual reflection.” Indeed, Doukhobors have long associated the Peshcherochki with the memory of ‘Lushechka’, as the much-beloved leader was affectionately known.

During the last five years of her life, I knew, Lushechka often withdrew here with her protégé, Petr Vasil’evich Verigin, whom she counselled on the teachings and traditions of the sect and imbued with the understanding and aspiration to fulfill his future role as leader. It was a matter of significance to Canadian Doukhobors, as descendants of the Large Party who followed him after her passing. Understandably, it was not mentioned by our hosts, being descendants of the Small Party who rejected his leadership.

It was no wonder why Lushechka was drawn to this place. There was something spiritual, powerful and beautiful about the grotto… something that inspired contemplation and communion with God and nature among all who came here. It gave rise to a sense of shelter and safety from the outside world, and brought about a feeling of comfort and solace from suffering.

These sentiments were echoed in the 19th century Doukhobor psalm engraved in the rock face above us as we exited the khatochka. It read (translated from Russian[1]) as follows:

“Be happy, o grotto, rejoice, o wilderness! For, herein is a refuge of the Lord our God, a true shelter and a comforting, protective covering - victory over my enemies and banishment to adversaries, weaponry against the unbelievers and hope to true believers. O, Thou Holy Mother of God, ever-present helper – in our misfortunes Thou hast been our devoted defender.”

According to tradition, Lushechka had these words inscribed on the wall of the Peshcherochki to consecrate it as a haven of peace and comfort, a place of sanctuary and sanctity for believers. It was unknown whether she composed them herself or whether they already existed in the repertoire of psalms forming the Zhivotnaya Kniga (‘Living Book’). Whatever their origin, they stood as a constant guide and enjoinder to all Doukhobors to gather here in fellowship, and to be happy and rejoice.

And rejoice here they had, over the ages.

“Doukhobors have long been coming here,” Yuri told us. “Since their arrival in the Caucasus in the 1840s, our people have met at the Peshcherochki every summer to pray, sing and eat together.” Indeed, among Doukhobors, the grotto was not only a sacred place of worship but also an important site of cultural celebration and social interaction.

I knew that in the 19th century, Doukhobors gathered here annually to celebrate Petrov Den’ – the feast of St. Peter celebrated on June 29th. This holiday held particular significance to them, as it was the name day of their leader, Petr Ilarionovich Kalmykov, late husband of Lushechka, who died in 1864. They would assemble in the grotto to pray, then spread about blankets on the plateau above and have a picnic. The young people gathered in a nearby hollow, out of sight of the stern elders, to sing and dance.

I asked Kolya whether Doukhobors still held Petrov Den’ at the Peshcherochki. “Some do,” he thoughtfully replied. “Those from Spasovka, Orlovka and other villages still meet here on that day.” Evidently, they were descendants of the Middle Party who recognized Verigin as leader but remained in the Caucasus. “But our Gorelovka people,” he clarified, “meet here on the first Sunday following Troitsa.” After Lushechka’s death, the Small Party and their descendants observed Troitsa (‘Trinity’) here instead.

This year, the Gorelovka people had postponed their annual Troitsa commemoration at the Peshcherochki by several weeks to coincide with our visit; a testament to their genuine goodwill and sense of brotherhood towards us.

Nowadays, I found out, it was not only Doukhobors who came to the Peshcherochki. It was also visited by Armenians, who set burning candles on the rocky ledges while praying to God here, as evidenced by the wax remnants we found throughout the grotto.

At this point, we left the grotto and Kolya led us to the banks of the Zagranichnaya where several lush, large berezy (‘birch’) and verby (‘willow’) trees were growing. “If you carefully break off the young branches,” he eagerly explained, “they will take root when planted. Let us do so, now, to commemorate our visit!” Following his lead, we each took turns planting saplings in the soft, marshy riverbank – a fitting, living testament to our journey here.

Thereafter, we slowly ascended back up the trail to the plateau above. It was here, on this windswept grassy plain, on a rocky outcropping some fifty meters from the edge of the gorge, that one of the most important events in the history of the Doukhobors took place 120 years earlier – the Burning of Arms.

On Petrov Den’ in 1895, Doukhobors gathered at the Peshcherochki as was customary. This time, though, members of the Large Party brought with them all the weapons in their possession, piled them together on the plateau above, then surrounded the pile with wood, poured on kerosene and set them on fire. As the weapons twisted and melted in the flames, the Doukhobors gathered around, prayed and sang psalms of universal brotherhood. It was a peaceful mass demonstration against militarism and violence.

This dramatic act of defiance had been carefully timed to correspond to the name day of Petr Vasil’evich Verigin, who became leader of the Large Party in 1887, while the site was deliberately chosen because of its deep religious symbolism. Indeed, it was aspired to evoke the words of the psalm inscribed in the grotto, years earlier at Lushechka’s behest, and solidify their importance.

For their part, Tsarist authorities viewed it as an act of rebellion. Two squadrons of mounted Cossacks were dispatched, posthaste, to the Peshcherochki to pacify the protestors and quell the civil disorder. Once they arrived, the Cossacks charged the praying crowd of men, women and children, slashing through them with whips. Many were brutally beaten and some severely injured when they were trampled by horses. The dazed and bloodied Doukhobors were then forcibly herded to Bogdanovka for questioning.

In the days that followed, Cossack troops were billeted in the Doukhobor villages, where they ravaged the homes of the Large Party, taking food, smashing furnishings, beating males and raping females without check or rebuke. Thousands were then banished, without supplies, to poor Georgian villages in oppressively hot and unhealthy climates, left to scrape by as best they could, or survive on whatever charity the local Georgians and Tatars dared give them under threat of arrest. Many perished in exile.

I felt a mixture of emotions as I reflected on these momentous events. It filled me with sadness that such a place of natural beauty and peace could have witnessed such needless cruelty and suffering. At the same time, I felt immensely proud and moved by the unwavering courage and steadfast faith that those Doukhobors demonstrated in the face of such adversity. And I felt a deep sense of gratitude for the legacy of faith, tradition and community they had imparted to us through their actions.

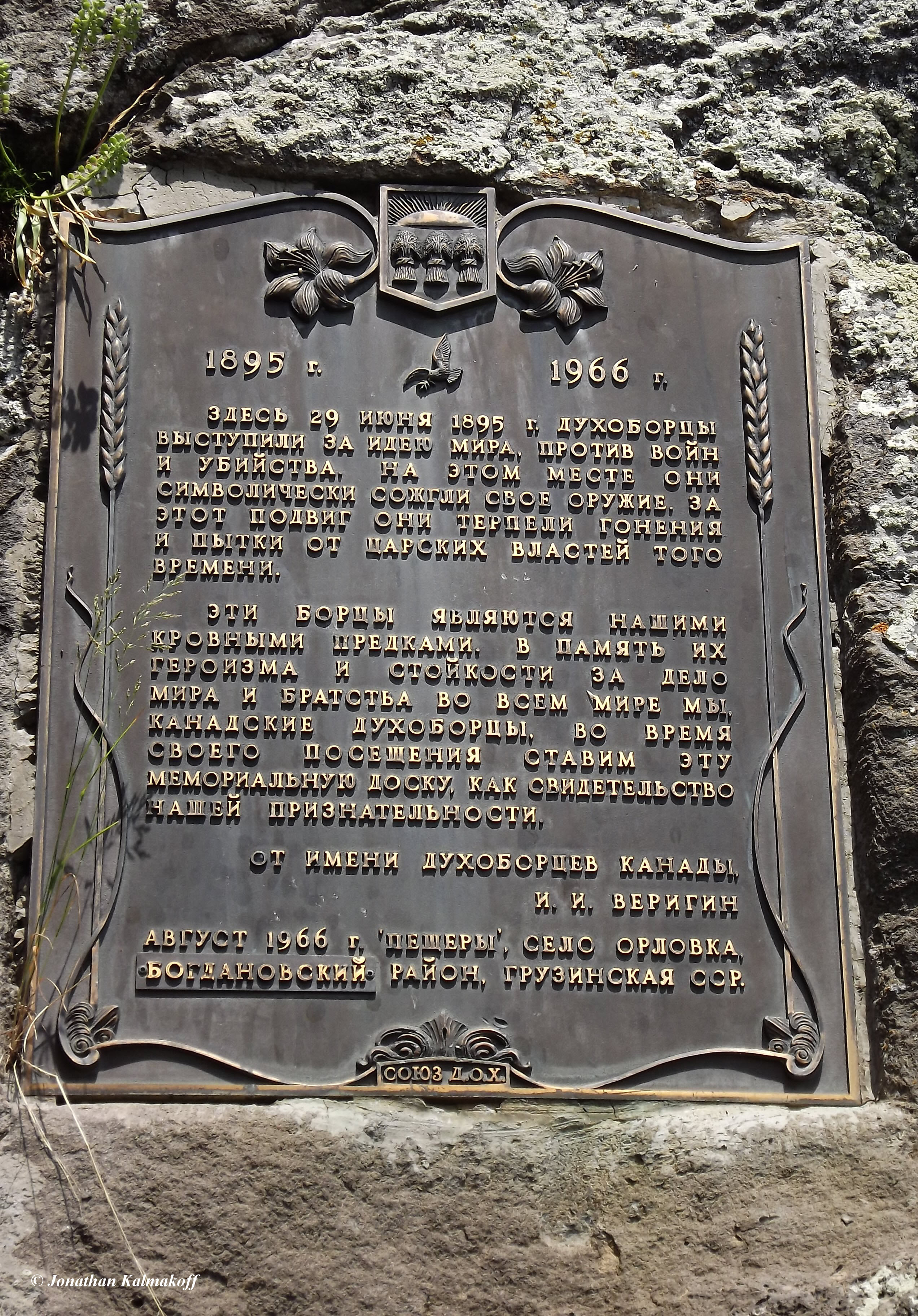

It was thus indeed fitting that the Burning of Arms was commemorated by a bronze plaque mounted on the walls of the Peshcherochki, which read (translated from Russian[2]) as follows:

Here on the 29th of June, 1895, the Doukhobors made their stand for the ideal of peace, and against war and killing. Upon this spot they symbolically burned their firearms. For this great deed they suffer persecution and torture from Tsarist authorities of that time. These peace makers are our own ancestors. In memory of their heroism and steadfastness in the cause of peace and brotherhood throughout the whole world, we, the Canadian Doukhobors, during our visit place this memorial plaque, in witness of our gratitude. On behalf of the Doukhobors of Canada, J. J. Verigin August 1966. ‘Peshcheri’, Village of Orlovka, Akhalkalak District, Georgian SSR.”

Once our entire group had reassembled on the plateau, our hosts spread blankets about on the grass, and after reciting the Otche Nash (‘Lord’s Prayer’), treated us to a picnic. It was a sumptuous feast – with cheese, bread, honey, roast chicken, sausage, tomatoes, pyrohi, green onions, watermelon, apricots and plums – all homemade and home grown by the Gorelovka Doukhobors.

As we broke bread together, Kolya relayed the ongoing efforts of Georgian Doukhobors to preserve and protect the Peshcherochki. “There are few of us left here,” he lamented, “but no matter how hard it is for us, we will live near this sacred place and care for it.” Several years earlier, we learned, the President of Georgia announced that it would be granted zapovednik (‘reserve’) status, thus entitling it to funding and legal status as a historic site. To date, however, the presidential decree had not come into force.

We assembled for a final group photograph at the rocky outcropping where the Burning of Arms took place and then departed for Gorelovka.

As we made our way back through the Javakheti countryside, I recalled that among her many prophecies, Lushechka had also made one specifically about this location, in which she spoke about Doukhobors returning to the Peshcherochki. This prophecy was published in William A. Soukoreff, Istoriya Dukhobortsev (North Kildonan: J. Regehr, 1944 at 64-65) in which it was written (translated from Russian[3]):

“The Doukhobors will be destined to leave our homeland and to stay in distant lands, to test their faith and to glorify the Lord, but I tell you, wherever Doukhobors may come to be, wherever they may end up going, they shall return to this place. It is their ‘Promised Land’, and when the Doukhobors return, they will find peace and comfort.”

Lushechka foresaw that the Doukhobors would wander far from this location, both physically (from the Peshcherochki) and spiritually (from the true understanding represented by the psalm inscribed there), but would inevitably return to both, thus ensuring the fulfillment of their sacred mission.

Indeed, our Doukhobor ancestors had left their homeland for distant Canadian shores, where their faith was sorely tested, many times. Most never returned. Yet more than a century later, we, their descendants, had journeyed to the Peshcherochki, gathered with our brethren who remained here, and together, found tranquility and solace in this sacred place.

Perhaps, in a way, Lushechka’s prediction had come true after all…

After Word

Special thanks to Barry Verigin and D.E. (Jim) Popoff for proofreading this article, providing valuable feedback, and offering translation assistance.

This article was originally published in the following periodical:

- ISKRA Nos. 2143, October 2019 (Grand Forks: Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ).

End Notes

[1]English translation of the psalm courtesy D.E. (Jim) Popoff.

[2] English translation courtesy ISKRA No. 1091 (July 8, 1966).

[3] English translation of prophesy (as published in W.A. Soukoreff) courtesy D.E. (Jim) Popoff.