Manitoba Morning Free Press

The year 1902 was a turbulent one for the Doukhobors in Canada. Disputes with government over homestead entry, internal dissension and zealot activity turned the tide of public opinion against them, prompting many wildly outrageous and grossly exaggerated reports. Despite this, some fair-minded Canadians continued to stand up unreservedly for the Doukhobors. One such citizen, E.H. Blow of Fort Pelly, Assiniboia, wrote a detailed and sympathetic account of the Doukhobors of the North Colony, extolling their prosperity and progress, social customs, skills, industry, work ethic, and charity, homes, buildings and yards, and other positive characteristics. Published in the Manitoba Morning Free Press on October 1, 1902, his message was simple and direct: Leave the Doukhobors alone. Give them a chance, and let them become Canadians on their own terms.

The peaceful, inoffensive, industrious Doukhobor has been the subject of much talk of late. This talk has been caused by the foolish utterances of idle and irresponsible people, and by the malicious statements of mischief makers. All the reports that have been spread abroad are either willfully false or grossly exaggerated. With the exception of his disinclination to observe three simple governmental regulations on account of his religious beliefs, there is no reason for complaint against him. He is a hard-working, uncovetous, and exceedingly charitable to all but when he has to rub shoulders with government, he becomes obstinate and fortifies himself with the instilled faith that God alone is supreme, and his laws only are to be observed. As the human Laws of all Christian nations today are based on God’s law, the Doukhobor cannot be regarded as other than an admirable character.

His present obstinate refusal to enter for his homestead, to register his vital statistics and to pay his road tax is no doubt annoying, but as some one has remarked “obstinacy is not to be commended but fidelity to what one deems to be right and proper is ever to be commended and recognized.” Leave the Doukhobor alone and he will soon became a citizen of Canada whose example in matters of industry and religious zeal will be worthy of emulation. The minds of the young men are turning in the right direction and victory will be with them.

It has just been my privilege to visit the thirteen Doukhobor villages in the Swan River valley, extending from Thunder Hill, eighteen miles along the Swan River, in Eastern Assiniboia, and the impressions that I formed from my personal contact with the Doukhobors and from my observations of their habits and customs is extremely favorable in their behalf. In the thirteen villages there are 2,500 souls, the population of the villages ranging from 100 to 250. These villages comprise what is known as the north colony.

Store Houses Filled to Overflowing

It is a little over three years since they settled on the land set apart for them by the Dominion government. They had no cattle, horses or implements to start with, but the good Quakers of the United States came to their aid and furnished them with means to purchase these necessary articles in a limited way. With primitive methods they went to work with characteristic energy and abounding patience and faith and today they have under cultivation an aggregate of 5,540 acres of which they have reaped this year a rich harvest of wheat, barley, oats, flax and vegetables, so that their store houses are filled to over-flowing, sufficient to place them, beyond all possibility of need for the next five years, supposing they did not wish to produce any more during that period. But they do intend to produce more, because they are now busy at work plowing the stubble fields and breaking new land. They had the wheat cut and stacked two weeks earlier than the English speaking settlers in the district and have a good part of their threshing done, not withstanding the fact that they have no modern machinery and do practically all their work by hand labor.

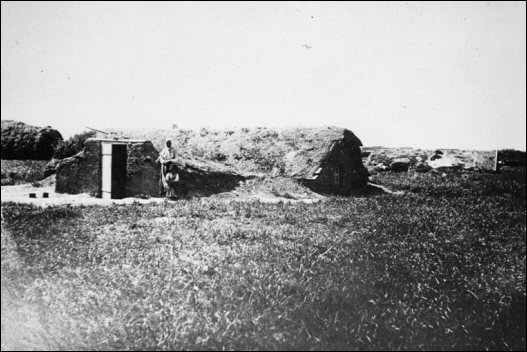

Village of Vosnesenya, North Colony, c. 1904. Library and Archives Canada C-000683.

The Doukhobor Homes

The Doukhobor villages and the Doukhobor home life are picturesque. It is like a bit of the old world transplanted into the newest. The cottages are ranged on either side of an open street and are tastefully constructed, presenting an attractive appearance. The material used in the construction of the houses is un-sawn spruce timber. Both the exterior and interior are plastered over with a clay mixture and then painted with a wash made of white painted clay, the prevailing white being relieved by dadoes around walls and posts made from a wash of yellow clay. The roof logs project over the walls and form verandahs which are neatly ornamented with woodwork, in some instances carved and scrolled. Beneath the verandahs on the sides of the houses mostly used are plank, stone or earthen platforms. Erected over the gates are ornamental arches such as are common in Northern Europe and eastern countries. The home yards are kept as neat as a palace walk by means of sand spread on the ground and watered and swept every morning, and once or twice during the day. The interior of the houses, with scarcity an exception are spotless. The walls and ceilings are immaculately white, while the tables, benches, and chairs all made of lumber fairly shine with the constant scrubbing and polishing of the good housewives. Generally speaking the houses each have a living and sleeping room, kitchen, and work and store room. In some cases where families live together under the same roof, the living and sleeping rooms are duplicated, both families using the kitchen in common. Where two or more families live together, they are usually relatives, the parents and their sons’ wives and children. The son always takes his wife to his father’s home and there they live until the young folks build for themselves, or if the husband has to go away to work, his wife and children are under the care and protection of his parents.

The Sleeping Apartments

A number of the members of a family may and do sleep in the same room. Because of this fact, some people are disposed to harshly criticize the Doukhobors, but it must be remembered that this habit is customary among the peasant folk of other European nationalities and thee are many pioneers in this country who can recall the time when Canadian settlers in their first homestead shacks were compelled to live in a similar way. Some of these settlers today are living in houses that cost from six to ten thousand dollars, and they will tell you not with a blush, but with feelings or pride, of the inconveniences they had to put up with in the early days, and how they overcame them. The Doukhobor is a God-fearing good-living moral man. No one can deny that. He who says to the contrary speaks with a false or foolish tongue. While to those who know naught to the contrary it may appear that there is no privacy in the Doukhobor home; there is privacy and above all there is sanctity. The Doukhobor believes with Canon Farrer: “It may not be ours to utter convincing arguments, but it may be ours to live holy lives; it may be ours to be noble, and sweet, and pure,” and so he lives by day and by night.

Clean Barns and Stable Yard

As neatness and cleanliness is the conspicuous feature of the Doukhobor home, so is with all about the homestead. There is a place for everything and everything is kept in its place. The horse and cattle stables are warm and clean. The manure is not thrown out of the stable and left there to contaminate the air or to pollute the earth. It is hauled away to the fields or otherwise disposed of. When the cattle come home at night, they are corralled some distance from the house and the feed is not thrown to them on the ground, but placed in racks, so that there may be no waste and no litter. Everything is neat and tidy and thrifty-like. Some settlers could get many useful sanitary and economic pointers by a visit to the Doukhobor villages.

Evidence of Taste and Skills

The large oven found in every house is an interest object. In its capacious interior all the baking and cooking is done, while sufficient heat is radiated from its ample surfaces to warm the entire house. On top the little children and old women have their sleeping place. The oven is kept scrupulously clean, the same as every other part of the house. Stoves are now coming into use in most of the villages. In every house visited there were plants in the windows, curtain draperies and little ornamental knickknacks of silk and woodwork, giving evidence of skill and taste on the part of both men and women.

Will Build Better Homes

The Doukhobor house is of a character that no pioneer in a new country need be ashamed of, but the Doukhobors are not satisfied. They have already expressed their intention of erecting larger and more substantial homes as soon as they get more land under cultivation. Their new homes will be chiefly of stone and each man will build on his own farm. Many of the men are skilled in the art of stone masonry, and as the shallow river beds in the region where they live abound in boulder stone, it is natural that they should decide to build their permanent homes of this excellent material.

The Women Spin and Weave

The ancient spinning wheel is found in every home and with it the women make yarn from the wool of their sheep and also spin flax thread, from which they weave coarse, serviceable cloth and also make twine, etc. The Doukhobors appear to understand the manufacture of hemp, and the industry among them should be encouraged. With improved machinery they could manufacture a number of merchantable articles, such as binder twine, rope and linen. What they are doing in this line now is on a small and crude scale. The women are skillful with the needle, their lace and silk work being very artistically designed and splendidly executed. The women also excel in basket making, the fancy straw baskets made by them being equal to anything ever imported into Winnipeg from abroad. This work they do, it would seem, for amusement, and generally to present to friends as souvenirs, though they turn it to profitable account sometimes. Some of the men carve animals and birds, and all are handy with carpenters’ and smithing tools. They are able to make anything they want out of the most unlikely material. The Doukhobor is by no means the stupid being hat some people think. Necessity has made him a genius. It has sharpened his wits and inspired his hand, and as soon as he feels that he is an absolutely free man he will become a model citizen. He has no vices; his wants are simple, and he follows the Bible precept that it is more blessed to give than to receive. He gives away one-tenth of what he produces, here again showing his strict observance of Biblical teaching.

Doukhobor women baking bread in outdoor ovens. British Columbia Archives E-07248.

Everybody Works

I have seen the people in their homes, in the fields, in the towns and on the trail. They are always at work, and everybody from the youngest to the oldest, finds something to do. Many hands lighten the burden, and their work seems to be a pleasure. The household duties of the women are light, owing to the assistance they receive from the young girls, consequently they accompany the men to the fields and help with what work there may be there to do. The outdoor work done by the women is voluntary. They go with the men more as a matter of comradeship and as the men are kind to the women, the latter are anxious to help all they can in sewing, caring for and reaping the crops. Many of the women who go to the fields do not join in the farm work, but take their sewing and knitting, with them. I have seen several groups of women of the various villages sitting around the stacks while the sheaves were being hauled in, or at the winnowing grounds, busily employed with their fancy work, while the children played about or occupied themselves with light employment. These scenes were very pretty and reminded one more of a happy family picnic party than anything else. Yet the work of the harvest was going on unceasingly and it was wonderful what a few men could accomplish in a day. Three stone flour mills are being put up in the north and south colonies, and the rivers are being utilized for motive power.

How the Doukhobor Threshes

The Doukhobor threshes his grain in the fields either with flails or by horses attached to corrugated rollers, the tramping of the animals and the pounding of the rollers separating the wheat from the straw. The threshed grain is finally cleaned by throwing it into the air so that the chaff and light foreign seeds may be blown out by the wind. The grain is then passed through home-made sieves and is then ready for mill or market. The process is slow but with the number of winnowing grounds in a field a lot of grain can be harvested in a day. I saw in one field a party of fifty men and women standing in a circle threshing with flails. It was a pretty picture of industry, the effect being heightened by the quaint multi-colored garb of the women. They sang as they worked, and were apparently as happy as school children.

Social Customs

The community system prevails among the Doukhobors. All moneys earned by the members of a village are pooled and each village has a common storehouse in which provisions and supplies are kept. Individuals may contract debts, but the village to which they belong becomes responsible for payment. All debts are promptly met, so that no business man hesitates to give the Doukhobors credit for any amount. Those who have commercial dealings with these people hold them in high esteem for their unfailing probity.

The marriage ceremony of the Doukhobors is simple. It is merely a declaration made before elders, but it is to them just as solemnly binding as any rite, ritual, or sacrament of the great church denominations. The story that a Doukhobor may divorce his wife at pleasure is untrue. The Doukhobor who does not treat his wife kindly, who fails to provide for her properly or deserts her is excommunicated, as it were and becomes a social outcast. To the Doukhobor, so firm in his simple Christ-like faith, this is a severe penalty as is rarely if ever incurred.

Cleanliness of person is one of the cardinal principles of the Doukhobor doctrine. The first house built in a village is a Russian bath-house which is used daily and in addition to this, men, women and children are frequently to be seen bathing in the rivers in nature’s attire. For the benefit of those who think this a depraved or questionable custom, the well-known motto of the British royal coat of arms may be cited. However, as the district becomes settled up and the Doukhobors become familiar with the customs of the country they will, no doubt, perform their outdoor ablutions in a more conventional manner. They would not wittingly give offense to any person.

The Doukhobor is Sociable

To the casual observer the Doukhobor might appear sullen and distrustful. But such is not his nature. He is merely respectful among strangers and training refrains him from being familiar. When approached, however, in a friendly spirit, he warms up and becomes sociable. He is full of good humor and wholesome fun. He bubbles over with a happy spirit. Children and adults are the same. The youngsters romp and frolic in the villages and have their play things, always homemade, the same as other children.

The warmth of the welcome that a stranger receives to the Doukhobor home is marked. There is no doubt about the genuineness of the hospitality. Gate and door are flung wide open and food for man and beast in abundance is instantly forthcoming if wanted. To offer payment for the entertainment is to offer insult. They will give but not receive.

Deeds of Charity

To illustrate the great Christian charitableness with which these people are imbued, it may be mentioned that they have frequently made gifts of animals and provisions to poor English speaking settlers whom they had accidentally learned were in needy circumstances. It is not long since that some of the villagers in the South or Yorkton colony, hearing that the house of an English speaking settler had been destroyed by fire, went to the forest, cut logs, hauled them to the unfortunate man’s farm and built him a new house and offered other material aid. One village also gave to Mr. Harley, Dominion land agent and Post master at Swan River six cows, with the request that they be given to any poor settlers that might be in his district. Many similar instances of exceeding generosity and kindness are on record. Charity is one of the virtues that the Doukhobor believes in exercising freely, and his charity is dispensed unostentatiously. When he sees opportunity to do good he does it as a solemn duty and without expectation of worldly favor or reward.

The North Colony Reserve

The north colony reserve is eighteen miles long and twelve wide, comprising six townships of 188,240 acres. The soil is uniformly good, being a rich loan. The land generally is what is known as highland prairie, much of the tract being open, but there are belts of excellent timber along the Swan River and in the hills. The typography of the country is attractive, being a succession of gently rolling hills, scored with ravines, which run back from the valley of the Swan River and furnish natural drainage. The Swan Valley west and north of Thunder Hill, is very beautiful. The banks in some places rise to a height of 300 feet above the meandering serpentine stream, and with treeless buttes and wooded dales present as lovely a picture of nature in its wild state as one could wish to gaze upon. The villages extend along the river southward from Thunder Hill, and are nearly all situated on the river banks, some on the north and some on the south side. Numerous spring creeks rise in the hills and furnish the purest of water. Some of these creeks run all winter and have never been known to freeze.

What can be said of the Doukhobor reserve may be said of the entire Swan River valley, so that the Doukhobors have no monopoly of the good things. There are thousands of acres of the very best agricultural lands west of the Duck Mountains, extending north from Shell River to the Swan valley, and westward from there indefinitely to the Saskatchewan country. This vast territory will soon be open for homesteading. Some of it already is, so that the Doukhobor reserve is but a speck on the map. The land between Swan River town and the first Doukhobor village just outside the province is a splendid district, and the Canadian and other settlers who have located there consider themselves very fortunate. The Doukhobors are well satisfied with their land, their only regret being that they cannot grow fruit as they did in Russia; but they have decided that it is more profitable and less trouble to grow wheat and buy apples. The country is overrun with small wild fruits. The Doukhobors are good farmers. They are careful and study the nature of the soil. When they acquire machinery, as they assuredly will as they grow richer, they will be big exporters of all kinds of cereals.

Doukhobor pilgrims leaving Yorkton to evangelize the world, 1902. Library and Archives Canada C014077.

Religious Zeal

The Doukhobors are intensely religious. Their zeal in this respect has recently created a nine days’ wonder for such it will prove to be. Some of the old men fearing that their sudden change from poverty to plenty might make them worldly, or that prosperity might cause the younger members of the community to relax in their faith, agitated for a thank offering to God, and advised that this offering should take the form of liberating their horses, oxen and cows. They also advised the renewal of vows not to kill or destroy life or use the product of any beast, bird or being that had been killed. The influence of the elders is strong. Obedience to the will of the elders is instilled into the Doukhobors from childhood, so it is little wonder that the strange propaganda had its effect. However, all the people were not carried away by the “craze.”, more than half of them refusing to give up their live stock or to follow any lead that made for retrogression. Less than 500 animals – horses, cows and sheep – were turned away from the two colonies of 4,500 people. A few sold their animals and bought implements. Those who declined to give up their live stock are among the most intelligent of the people, who recognize the advantages of having horses and work cattle for the carrying on of their agricultural pursuits. This faction will continue to add to their live stock and implements whenever they can afford it, and in fact were among the buyers at the sale of the Doukhobor cattle at Fort Pelly last Wednesday.

Will Result in Good

This wave of religious zeal will do good. It will probably result in the solution of the little difficulties that have been encountered with respect to the observance of the governmental regulations already referred to. There are already signs that this will be the effect. The factions are now at outs with each other, and the progressive spirits will break way from the prevailing communistic ideas and will strike out for themselves. When the others see how well these succeed they will fall into line. They are thinking and debating, and discussing and all will end right, because the young men who are breaking away are now just as stubborn as the elders, though it causes them many a heart pang and brings down upon them a species of petty persecution that under the circumstances requires a strong will and much moral courage to withstand. The two factions are known among themselves as the “bad Doukhobors” and the “crazy Doukhobors.”

The Passing of the Craze

When the Doukhobors became affected with the craze, they discarded their boots, woolen stockings and every article of clothing made wholly or partly of leather or wool. They bought rubber boots and made shoes of planed binder twine with wooden soles. They took the leather peaks and bands from their caps and replaced them with cloth, and took the place of the horses and oxen at the wagons and plows. They are getting tired of this practice now as it evidenced by the remarks that the “bad Doukhobors” let fall occasionally among their English speaking friends; and I saw myself people from one of the villages who had turned loose their sheep, hauling sacks of wool home from Swan River. This is indicative of a recantation which all who are in touch with the situation, believe will soon become general. They probably realize that their extreme self-abnegation before God involves altogether too much punishment of the flesh without corresponding benefits to the soul. No one minds if they do make cart horses of themselves. That is their own business.

Some may think it cruel to have the women helping to pull the wagons, but the women do this of their own accord and against the wishes of the men, and the loads are so light, compared to the number of men and women who do the hauling, that the individual work load is light. As they march along the road they sing joyful songs and laugh and joke one with the other. The women do not hitch themselves to the wagons in all cases. They accompany the men to town to make purchases and to prepare the meals at the roadside camps, and may frequently be seen on the trial, walking ahead while the mean pull the wagons and carts. No argument can convince the Doukhobor that he is wrong in giving up his horses and cattle. When cornered by a Bible quotation, he repudiates the Old Testament, falls back on the New, and finally tells you that he gets his teachings and inspirations from the Book of Life. The Doukhobors are not the only people who are carried away by religious fads. Only a few months ago in Winnipeg then were men and women who gave up all their money and land to join some Bible school that was conduced by a Yankee on Broadway and there are several other sects in the city whose religious practices are so emotional that they partake of the nature of mania.

Objections to Government

The Doukhobor does not believe in government. He recognizes but one ruler and that is God. “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof” and therefore, he must not lay proprietary claim to anything in the earth, under the earth, or in the sky. Hence his objections to the making entry for his homestead, to pay road tax, and to the registration of vital statistics. He will build roads, but he wants no government supervisions; he is willing that the homesteads be entered for in the name of the village, but will not agree to individual ownership. He would also report the births, deaths and marriages, but fears that that means taxes and taxes mean government. He is afraid that compliance with these simple but important regulations would be the inserting of the thin end of the wedge and the end would be tyranny. He does not understand, but soon will. The government will find means to convince him that he has nothing to fear and the example of those of his brethren who have homesteaded, will have a salutary effect, though it may be slow. It took the children of Israel a whole generation to realize and appreciate the benefits of their release from thralldom, and so it takes time with all people who have been subjected for centuries to the falling yoke of despotism, and have learned to hate their oppressors with a bitterness that knows no bounds to get rid of their prejudices, their fears, and their doubts. It is safe to predict that before next spring the number of Doukhobors to take up their homesteads will largely swell the present list.

Doukhobors plowing, North Colony, 1905. Library and Archives Canada A021179.

The Doukhobors Developing

The Doukhobors are developing. Those who saw them arriving in Winnipeg a little over three years ago would scarcely know them now. Many of them have laid aside their national peasant garbs and adopted Canadian attire. They young people want to get on: it is the elders who cling tenaciously to their old habits, customs and beliefs, just the same as the old men of those excellent people the Mennonites cling to theirs and urge the young people to do the same. But with the progressive influences surrounding them, neither the young Doukhobor nor the young Mennonite can be checked. The Mennonites have been in Manitoba nearly 30 years, but yet their advance towards that goal which Canadians desire to see them attain is only beginning to be noticeable. It will take another generation to evolve the real thing.

Not a few of the Doukhobors can now speak English, especially the young lads. Several boys have been employed as store clerks in Swan River town, and a couple are engaged there now. The merchants speak highly of their ability as salesmen, and of their energy and faithfulness to duty. They are bright and quick to learn, mastering all the details of counter work in a few weeks. These lads are well dressed and if they were placed with a group of Canadians, any one who did not know them, would not be able to identify them. I have watched the immigration of foreign peoples since the arrival of the Mennonites, and in my opinion the Doukhobors are equal as agriculturists to the very best Europeans of the peasant class that have come to this country and much better than a good deal of it. They are self reliant, good providers, and will never cost the country one cent. Some of those who stubbornly cling to their belief may perhaps endeavor to seek an asylum where they will be allowed to follow their peculiar ideas regarding government without interference, but there will be few.

Not Illiterate

It is frequently asserted that the Doukhobors are illiterate. This is not a fact. The majority of them can read and write in their own language, even the young boys can read and I have frequently seen them reading letters and the tracts received from a Russian committee that has headquarters in London, England. They Doukhobors do not favor the establishment of English schools, but teach their children at home. Every father is the teacher at his own house, and also the preacher. The children are taught the unit system of reckoning by the use of the abacus, such as the Chinese use for calculating. The Bible is the only book seen in their homes, but they receive papers and tracts from abroad.

How the Doukhobors Came

An impression has gained ground that the Doukhobors were brought to the Northwest at an enormous expense to the Dominion government. This is erroneous, as most of the reports about these people are. The Doukhobors were sent to Canada by money provided by the Society of Friends in England, and the Quakers of the United States furnished money to buy them seed grain, live stock, and implements. In two or three trifling cases the government did advance money for implements, but on making inquiry I ascertained that the amount has been repaid. The per capita bonus paid to European steamship companies for promoting emigration, was given to the Doukhobors as the steamship agents had not worked among them and waived their claim. Part of this money was used in purchasing food supplies under the direction of a committee of local gentlemen. Considering the expenditure for advertising, agents, etc., the average British immigrant costs per head vastly more than the Doukhobors did. I am informed that all inducements given to the Doukhobors are open to any large bodies of desirable settlers from any other part of the world.

As to the character of the Doukhobor, his industry, his morals, his charity, I am glad to state that the opinion I have formed in respect thereto is shared by the business men of the towns where they trade and by those who have had occasion to come in contact with them in matters of business or otherwise. One business man said: “If they will only leave the Doukhobors alone until they get to understand things here. They will make a veritable garden out of this country.”

Not All Alike

The people in each village have their own little fads about dress and edibles, and sometimes the people of the same village hold diverse views about these things. Now, regarding the turning away of their live stock, only a certain percentage in each village have done this. Out of thirteen villages that I have visited there were only two that had no horses, oxen or cattle. In the others more than half of the live stock has been retained, and as I have said more will be purchased by the independent men as soon as they can get the money. In every field passed, I saw more men at work with oxen and horses. I saw no women pulling plows or wagons on the farms. Some won’t eat butter; others will, and I saw the women making excellent butter. Meat in all forms is tabooed, but fish has a place on the bill-of-fare in some homes. However, a straight vegetarian diet is the prevailing rule, and it seems to agree with these people, for they are stalwart, healthy and strong. The children are the picture of health. They would make fine illustrations for health food advertisements. Disease is rarely known among them. Both men, women and children are comfortably clad, and in all the colonies there is every appearance of comfort, happiness and prosperity. Leave the Doukhobor alone. Give him a chance and he will soon evolve into a sturdy, worthy Western Canadian citizen.

E.A. Blow

Fort Pelly, Assiniboia

September 26, 1902.

Special thanks to Corinne Postnikoff of Castlegar, British Columbia for her assistance with the data input of this article.